When I first dumped my old life as a successful foreign correspondent to make my way out to Hollywood, I wasn’t supposed to end up alone. My brother and sister both lived in town; my best friend from back in junior high had settled down here; and an old college pal had come out years earlier to try to make it as an actress. Shortly after my arrival, however, my brother up and moved to Micronesia and had two children I’ve never seen; my sister got married and moved to San Diego; my oldest friend passed away; and the actress decided she’d had enough, moved to Houston and landed herself The Dreaded Real Job.

When I first dumped my old life as a successful foreign correspondent to make my way out to Hollywood, I wasn’t supposed to end up alone. My brother and sister both lived in town; my best friend from back in junior high had settled down here; and an old college pal had come out years earlier to try to make it as an actress. Shortly after my arrival, however, my brother up and moved to Micronesia and had two children I’ve never seen; my sister got married and moved to San Diego; my oldest friend passed away; and the actress decided she’d had enough, moved to Houston and landed herself The Dreaded Real Job.Maybe I should have taken all this as yet another sign that My Big Deal Hollywood Life simply wasn’t meant to be. But most of them check in from time to time to see how I’m doing—even the dead one, who often shows up in my dreams “Shuffling Off To Buffalo,” a step the two of us picked up in our eighth grade tap dancing class.

Meanwhile, the Actress Friend Who Gave Up called last night to tell me she’s tired of her new life as a wine broker and wants to do something important. Wine is important, I tell her. I would have to list it among the top five most important things in my world, and I can’t even afford the Trader Joe’s label any more. I'm considering nipping at the cooking sherry like some fifties housewives in that Todd Haines movie with Julianne Moore.

“Part of me feels there has to be more than this,” she sighs. “Have you heard about ‘Teach America’?”

That movie sucked, I want to say. Who wants to watch a couple of stop action figures go at it for two hours?

That movie sucked, I want to say. Who wants to watch a couple of stop action figures go at it for two hours? But then it turns out she isn’t talking about Team America. She’s talking about a Princeton-based program meant to save the nation’s underprivileged youth from a lifetime of ignorance and poverty. She tells me a big part of her, the part that isn’t paying a mortgage and an Ikea revolving charge account, wants to change the world.

What was this? Here was the daughter my mother never had who’d come to her senses and gone off to make a decent life for herself. Her new house wasn’t even built when she bought it, so they let her pick the floor tiles and a selection of upgraded appliances. She got to intermix slate with a blanket of flawless sod in her front and back yards both. She has an expense account and an assistant. She goes on business trips to France and Napa. She gets to eat all kinds of free cheese.

“I don’t understand,” I tell her. “You were supposed to be my hero.”

“You were supposed to be mine,” she says when I tell her about my latest abject failure to land a Big Deal Screenwriting Job. “You have to hang in there, you know.”

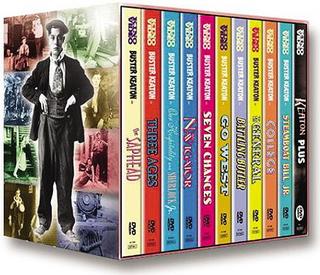

What she means is I have to do it for her. I have to do it for all of them who took their balls and went home—even the ones I never met. I’ve always felt the spirits of these sorts of folks cheering me on as they buzz about my house. It was built in 1929 as studio housing back in the day when people like Buster Keaton were turning Hollywood into the preferred destination for moviemaking. East Coast actors were lured out with a one-year contract and a little bungalow house for one. After that, they either moved up, moved out, or headed for the hills to jump off the letter “H” in the Hollywood sign.

They’ve been expecting an awful lot from me, all these dead people, since the day I moved in with my two hundred-pound Neopolitan Mastiff, Bunny, who sniffed out their collective presence in virtually every corner. He joined them a couple of months later—the day after I won a Big Deal Screenwriting Competition—and I’ve always felt he wanted to make sure I’d be alright before he died. I was babysitting my sister’s new Wiener Dogs the night I took Bunny to the veterinary hospital and a nurse came out, alone, handing me his collar. I never gave the wieners back.

“How are the puppies?” my Actress Friend wants to know.

“They’re ten,” I tell her. “That’s seventy in dog years. It’s like living with a couple of bitchy old women.”

She decides what I need is a visit to Houston, where I will be properly wined and dined and I can sleep in the brand new guest room she’s managed to decorate by tuning into the design channel exclusively. I’m not crazy about traveling any more, and part of me wonders why she can’t come back to L.A.

She decides what I need is a visit to Houston, where I will be properly wined and dined and I can sleep in the brand new guest room she’s managed to decorate by tuning into the design channel exclusively. I’m not crazy about traveling any more, and part of me wonders why she can’t come back to L.A. The other part knows why. Maybe dreams don’t die, after all, they just turn into new ones that continue to seem just that far out of reach. I guess another thing they won’t tell you in film school is that giving up and going home is never as easy as it looks.